Sermons and other resources from our time together.

Wrestling with God

Jacob’s night-time wrestling match with a mysterious stranger is one of the most puzzling and mysterious stories in Scripture. But, sometimes, life is like that. Suffering strikes you down out of a clear blue sky. And then what?

Doubt is Faith's Wingman

Not only is, or at least was, Top Gun “the most dangerous film of 1986” it also has important things to teach us about faith and doubt. What, for instance, does it even mean to believe? And hence, what does it mean to doubt? Is it always bad? Can it sometimes be good?

Easter and The Two Trees

Nick Cave once sang “I don’t believe in an interventionist God, but if I did…” We live in a culture that has dismissed God but has left a God-shaped hole behind. The triumphant claim of the so-called New Atheists of the first decade of this century that “religion ruins everything” has given way to something much more like’s Nietzsche’s cry that “God is dead, and we have killed him.” Not a cry of triumph at all, but something much more ambivalent. We have killed God - but what have we replaced God with?

Christmas and the Meaning of Life

What on earth does Christmas have to do with the Meaning of Life? Is there any substance behind the tinself?

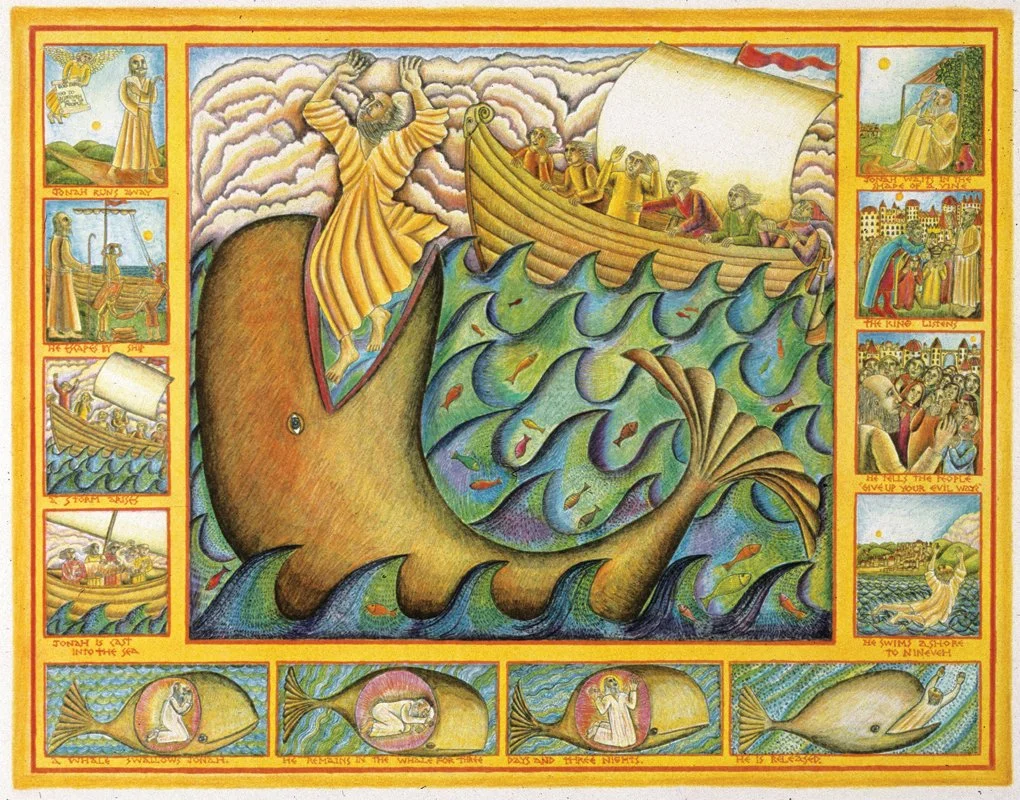

Jonah and the Whale

One of our running jokes is that every evening has to end with something whale-related. At one level, it’s just a joke, but at another level, it turns out that many of us cherish the story of Jonah and the Whale. It’s such a powerful story, and it opens us up into something much more powerful than picking out a kernel of “the moral” and throwing the husk away. We want to live into stories like this, live into the reality in which, no matter what happens to us, God is faithful.